Movie Equations — what’s even a blockbuster anymore?

How much does a movie really "make" when it's on a streaming service?

There are two things I really, truly despise in this world: eggs (because eggs have tried to kill me throughout my relatively short life so far) and empty boasting from companies about how well a movie or TV show has performed.

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’re probably aware of the boasting I’m talking about: streamers like Hulu, and companies like WarnerMedia or Amazon sending out PR blasts about their latest achievements. Here are just a couple that I quickly collected:

Apple TV+ saw its best weekend since the streamer debuted 15 months ago, seeing a 33% increase in viewership with the release of Justin Timberlake’s Palmer, according to Variety.

From Hulu: “Happiest Season earned the number one spot on Hulu, as the romantic comedy was the most-watched film across all acquired and Hulu Original films during its opening weekend. The hit holiday film also generated the highest engagement with Hulu subscribers.”

Then there was WarnerMedia, which touted “nearly half of the platform’s retail subscribers viewing the film on the day of its arrival, along with millions of wholesale subscribers who have access to HBO Max via a cable, wireless, or other partner services” for Wonder Woman 1984. That’s better than the rest, but then it leads right into this quote from executive Andy Forssell: “Wonder Woman 1984 broke records and exceeded our expectations across all of our key viewing and subscriber metrics in its first 24 hours on the service.”

Finally, for WarnerMedia’s newest film, The Little Things, which was released in theaters and Forssell had this to say for the movie’s performance on HBO Max: “We are absolutely thrilled by how Warner Bros.’ The Little Things is performing on HBO Max — it immediately shot up to number one, where it currently remains.”

It’s all hogwash.

Box office reports are never perfect, but over the last hundred years, the studios and exhibitors have figured out a system of releasing information to the trade publications (like Variety) and the general public at large. Once the internet came around, and sites like Box Office Mojo began making that data even easier to access, weekly box office stories took on a whole new life. Ask any studio executive and the answer tends to be the same: they loathe box office reports until they’re sitting on top of the throne. It’s impossible to hide from a film’s performance at movie theaters — the data is too easy to collect and the industry is built on decades of relationships built around those data sets.

Streaming, however, is a whole new moment. The studios don’t have to report anything, and they own the distribution. No one has to know anything unless the studios want them to know something. So, we get statements like “the film has exceeded our wildest expectations” without knowing what that means. Did executives predict one million people would sign up for HBO Max to watch Wonder Woman 1984 or Soul, and with two million subscribers their expectations have been exceeded? Or did they expect 250,000 signups, and get 300,000 signups? I have no doubt that movies like Wonder Woman 1984, Soul, and Palmer performed well — or that TV shows like The Flight Attendant and A Teacher are bringing people into the platforms.

From an executive’s perspective, it makes sense. Why bother doling out numbers, especially if those numbers aren’t extraordinary. Not just good, not great, but extraordinary. Anything else becomes the story. It’s unavoidable. If a studio’s job is trying to get as many people to watch a movie within its first 10 weeks of release, having the first three weeks dominated by “you know, I thought more people would show up for this” stories isn’t exactly the press executives want to see.

Let’s use the “billion dollar movie” as an example. If a billion dollar movie equates to roughly 109.2 million tickets sold ($9.16 for average ticket price), and we assume that one Netflix stream accounts for at least two viewers based on the average number of people per household in the United States (2.53), then a movie that generates 54.5 million streams is about $1 billion. There are several Netflix movies that accomplished this; Murder Mystery (83 million), Six Underground (86 million), Bird Box (89 million) and Extraction (99 million) to name a few. By that simple math, Extraction would have made $1.63 billion. That’s roughly the same as Disney’s Lion King remake ($1.65 billion).

Still, knowing that 99 million households watched at least two minutes of Extraction within the first four weeks of its release doesn’t necessarily equate to $1 billion. Of those people, how many would have ventured out to watch it in theaters for $9.16 (or more)? How many subscribers only watched it because it was readily available on Netflix, a streaming platform they pay $14 a month for, and heavily promoted at the top of the page?

That’s the billion dollar question.

The comparison we’re trying to determine is the drivability of movies to streaming services on par with a film’s drivability in theaters. How much is this movie driving people to spend money versus how many people are watching this simply because it’s here? Unlike a big theatrical release, stream’s goal is to keep people month after month. People spend the initial $14 a month to watch a new, big thing (either a TV show or movie), but continue paying because they’ve sunk their teeth into something. Using a movie like Wonder Woman 1984 is more likely to bring in subscribers than a random title, while The Sopranos and Game of Thrones or Sex and the City keeps people coming back.

(There is one major hurdle: China. We’re going to have to figure out for streaming exclusive titles (like stuff on Netflix) is the lack of release in China. The country’s box office was the biggest worldwide in 2020, and in 2019 represented 40% of total global box office revenue. For now, we’ll focus specifically on the US, somewhat problematic considering more than 50% of Netflix’s entire subscriber base is based internationally.)

With that in mind, how do we determine what actually does well on streamers like HBO Max, Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+, and Hulu? What is the true equivalent to a billion dollar film — including the driving factor, not just number of streams — on Netflix?

More importantly, does Netflix need a string of “billion dollar movies,” or just a consistent enough string of flashy movies on top of TV shows, specifically targeting keeping subscribers in countries where saturation levels are close and acquiring new ones in countries where acquisition is still greatly rising? No. Does HBO Max, a newer service with a great library that will likely keep subscribers but touts a costly price tag and is still struggling by Wall Street standards to get people onto the platform in the first place? More likely.

Remember: retention is a library game, but acquisition is an originals game — and leaning on certain types of films can help in that specific area.

It’s impossible to try and determine exact numbers for a film on a streaming service that’s available in several different countries (see Soul or Spenser Confidential) without access to that data. But we can try and determine whether or not a movie is actually generating the same kind of response that a $1 billion action movie or $150 million teen romcom success would in theaters. There are some tools that I use, including:

Google Trends 10-week performance for a movie’s release date

Nielsen data

Self reports — with numbers

Earnings reports

To be clear: None of these tools will help convert to any specific data points about how many people signed up to watch a specific movie. Instead, we can use it to get a clearer picture of how much potential value a movie brings to those streamers. If the obviousness of that value is particularly high, it’s a little safer to assume said value translates to revenue.

Google Trends

Google Trends is sometimes frowned upon, but to me it represents an interesting data set for two reasons — I can track interest in the movie over the course of a set time (10 weeks in the chart below, which is reflective of a primary run in theaters) comparing that to box office data, and can help me determine for my own interests what studio executives might decide to do with streaming platforms and shorter theatrical windows. Let’s use Wonder Woman and Wonder Woman 1984 as an example.

The first chart below is a 10-week summary of search interest in Wonder Woman between June 2nd and August 10th 2017. There are five or six noticeable upticks in interest co-relating to various weekends. The data suggests to me that people are likely googling playing times for the movie at their local theaters and checking out reviews or “is there a post-credits” scene post to help them decide if they should stick around after the credits start rolling.

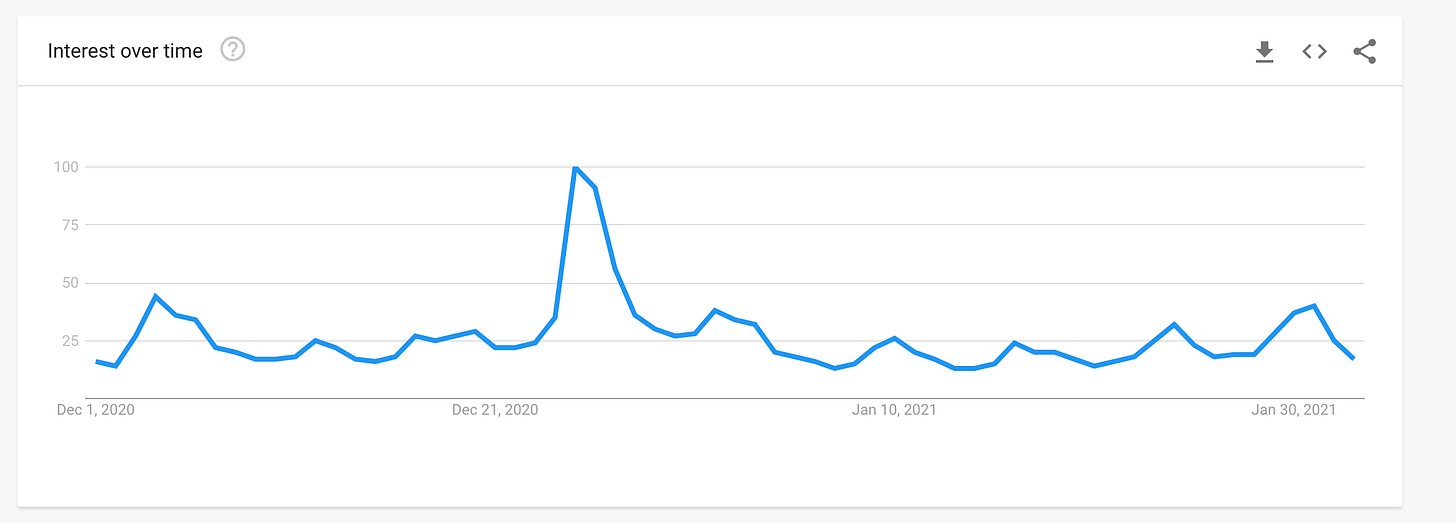

The second example is Wonder Woman 1984. The data runs from December 25th through February 3rd — less than 10 weeks, but the most up to date available trend data. Unlike Wonder Woman, Wonder Woman 1984 sees a continuous decline from its second week on. With COVID-19 and less theaters open, as well as its availability on HBO Max, there are likely less inquiries for showtimes. Negative reviews may have impacted people who were going to sign up for HBO Max or go see the film otherwise in its second and third week, but it’s more likely that anyone who was going to watch the film would have done so over the 10-day holiday period.

Search results for HBO Max in the United States between December 1st, 2020 and February 3rd, 2021 also support interest in Wonder Woman 1984 being relatively short, with higher peaks likely more closely associated with average viewing of TV shows and other films. Data from Box Office Mojo supplements the data, with a steady decline in revenue and, seemingly, general interest.

Nielsen

While Google Trends can tell us general interest in a film over a certain period, for a platform like HBO Max its third party-data from firms like Nielsen that help give a clearer picture. Quickly reiterating that Nielsen has its own flaws that can’t be ignored, it’s also unfortunately the best option we have. Nielsen doesn’t currently track HBO Max in its OTT roundups, but the firm made an exception for Wonder Woman 1984. The film was watched in its entire roughly 14.9 million times within its first weekend, according to the firm.

That’s less than Soul (15.6 million complete plays roughly), but correlates to the Google Trends spike. People were interested in a big movie, available to them over the holidays, and they watched. Other questions, like how many of these are repeat viewings (therefore equal to one subscription) or how many people would have seen it in theaters if not for the HBO Max availability? Those we don’t know, but with Nielsen data, we can do a little more analysis (thankfully).

Some quick math: 14.9 million times the average ticket price in the US of $9.16 is roughly $136.5 million. If we add the $39.2 million the film has amassed domestically right now $175.7 million. Since HBO Max is only available in the US, it’s the best way to calculate a full theatrical release vs streaming option. If there was no HBO Max option, and if 50% of those who watched Wonder Woman 1984 on HBO Max went to theaters (even with LA and NYC closed), the film may have generated an additional $68.25 million in theaters. That’s just over $100 million domestically. Peanuts for a movie like Wonder Woman 1984.

Here’s where Nielsen data acts as a supplementary tool. We can take some of the brief information given to us by WarnerMedia and incorporate that with Nielsen’s data — taken over Wonder Woman 1984’s first weekend — and determine some more data points.

Related: On top of Nielsen, using data firms like Antenna, Reelgood, App Annie, Sensor Tower, and others will help to give a clearer picture, even if they don’t have full numbers. They should be used to supplement a theory or prediction.

Self reports

Two days after Wonder Woman 1984 was released, WarnerMedia announced that “nearly half of the platform’s retail subscribers” viewed the film “on the day of its arrival.” There are two data points for this that we can pull from: at the end of October, WarnerMedia announced that HBO Max had 3.6 million retail subscribers. By the time that AT&T CEO John Stankey held the company’s fourth quarter earnings call in January, that number increased to 6.8 million. The quarter closed at the end of December 2020. That means between the end of September and the end of December, retail subscribers doubled.

I’ve written about this before, but I believe that retail subscribers are some of the most important. Unlike activations, which refers to customers who are eligible for upgrades and are activating their accounts, retail subscribers are people actively seeking out and paying $15 a month for the service. Now, if “nearly half of the retail subscribers (and for this, we’ll lean closer to 8.6 million because Wonder Woman 1984 came out on December 25th) watched the film day-of release, that’s about 3.4 million, or all of the last two quarter’s subscribers combined. Add in the number of activated accounts, which jumped from just over 8.6 million activations to 17.17 million, and you get a total of about 11.5 million subs. When we compare that to Nielsen’s 14.9 million views, adding in for a margin of error that comes with estimating, it all seems to add up.

Earnings reports

All of which brings us to our final piece of the puzzle (in this scenario — the fun thing about equations is they change all the time with more information): earnings reports.

This isn’t a full proof solution either, as The Entertainment Strategy Guy points out on his website. Also, remember that earnings calls exist for the sole reason of executives telling investors, shareholders, the press, Wall Street analysts, and potential investors that everything is going well and people should buy into what they’re doing. Well.

The bigger question with streaming is how many of those roughly 8-11 million people who likely came for Wonder Woman 1984 remain subscribed to the platform in one, two, or three months. AT&T CEO John Stankey told analysts that while they might see “a little bit of spikiness,” the company also wasn’t “going to see the kind of subscriber spikes we saw in December and early January” adding that “isn’t part of the plan.” Instead, Stankey said, the goal was to keep consumers happy with a number of new movies.

“What we've seen at the front end with the numbers, what our experience has been, we've been delivering what we expected....and we feel pretty good,” Stankey said.

Again, acknowledging that earnings calls are sale pitches, a significant subscriber spike based on Stankey’s words could co-relate to the other data points listed above. Wonder Woman 1984 drove a significant amount of HBO Max subscriptions. The real story now, to see if Wonder Woman 1984 did what it was supposed to accomplish as a streaming first title, is whether those customers stick around. We’ll have to wait and see — and even then, we’ll have to do some digging as new movies will likely bring in smaller batches of subscribers and activations.

Bottom line

This is ridiculous. It should not be this difficult to figure out how well or how poorly a movie performed. I understand why it is. I also understand why executives would make it even more difficult to suss out if they could. But without numbers, it’s impossible to say what’s a guaranteed blockbuster. But that’s why things will inevitably change.

Look to the talent agencies and look to the unions. “Movie star” is more than a symbol; it’s a negotiation tool when actors or directors or writers sign on to a project. Actors and directors became stars through movies that over performed at the box office. Without those numbers, it’s impossible to say for certain what value a movie star brings to a streamer, and therefore harder to negotiate. Even with internal numbers shared with creatives, it was public box office data and headlines like “Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese do it again” that reminded the public of true star power, getting them into seats.

Things will change. Data is power, and public data is used as leverage on behalf of talent in negotiation talks. For now, we have to figure out a way to determine what’s a hit and what isn’t. It’s pretty clear that if Warner Bros. had released Wonder Woman 1984 in theaters it wouldn’t have done superb, even by new standards. As a streaming title, however, it seems like it did its job. Hopefully, we’ll get more transparent data from WarnerMedia, and AT&T, soon enough.